How Singapore became a global center of cell-based meat.

How Singapore became a global center of cell-based meat.

In 2018, a food-science startup in Singapore announced a scientific breakthrough: the ability to produce shrimp from stem cells. “The greatest challenge to creating cultivated seafood is that there is no existing science about how to do it,” says Sandhya Sriram, a co-founder of Shiok Meats (“shiok” means “delicious” in Malay slang). “So we started from scratch.”

For years, cell-cultured meat, real animal muscle that is made from cultivating cells, has been on the rise. As the unsustainable nature of traditional meat production becomes clear, cultivation is an increasingly popular alternative to produce food that is better for the planet. Since a Dutch scientist first introduced a hamburger made from stem cells in 2013, the industry has grown to include over 60 companies around the globe, part of the larger sector of alternative proteins—including plant-based meat, egg, and dairy products. Cultivated meat and fermentation companies devoted to alternative proteins have attracted over US$5.9 billion in investments, with US$3.1 billion of that amount in 2020 alone. The competition has become so heated that it’s even been called the “edible space race,” with cell-based meats—including kangaroo, bison, and even cow muscle tissue—that were produced on the International Space Station.

Yet, until 2018, one type of protein remained uncultivated: shrimp.

So Sriram and Ka Yi Ling, both stem-cell biologists, started a company that would focus on the diminutive crustacean, a key ingredient in many Asian countries’ cuisines, and launched their endeavour in the global hub for innovation and entrepreneurship in cellular agriculture: Singapore. The 281-square-mile island state, with 5.5 million people, currently imports over 90 percent of its food from 170 different countries and regions. To reduce its reliance on imports, the country launched “30 by 30,” a pledge to produce 30 percent of its nutritional needs locally by 2030—up from less than 10 percent today. Singapore is spending US$107 million to research and develop sustainable urban food production, with US$44.5 million devoted to an Agri-Food Cluster Transformation (ACT) Fund that helps create farming systems that are more productive, more resilient to climate change, and more efficient.

“As a resource-constrained urban city-state, global concerns on food resilience are more critical for us,” says Damian Chan, Executive Vice President of the Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB), the government agency responsible for strategies that enhance the city-state’s position as a global centre for business, innovation, and talent. “Against the backdrop of global trends such as climate change and population growth, agri-food technologies allow us to produce more with less, and Singapore hopes to become a global leader in developing food that can sustainably feed the world.”

As part of that goal, the country’s Singapore Food Agency (SFA) became the first national regulatory body to approve the sale of a cultivated-meat product in 2020. In the process, the island nation took a giant step forward in helping to rewrite the future of food. “I wanted to create a more ethical food, and Singapore is the perfect ecosystem for startups,” Sriram says. “It offers governmental support with grants, has an international workforce of highly educated employees in tech and science, and is truly supporting this industry. It’s so exciting to be making new food for the future.”

Since gaining independence in 1965, Singapore has grown to become an international leader in innovation and entrepreneurship, thanks to its mix of industry-engaged research institutions, a strong pool of local and international talent, and forward-looking government regulation. It’s also home to cutting-edge infrastructure, including the A*STAR-Temasek Food Tech Innovation Centre and the ADM-Temasek microbial fermentation facility. With the support of the EDB, tech and science companies are now increasingly setting up shop in Singapore to develop new products, tap into the country’s business-friendly environment, and orchestrate their expansion into Asia.

In particular, Singapore has become the global leader in the fast-rising industry of agri-food technology. From international brands to local startups, agritech companies are revolutionising the future of food in Singapore and beyond. Perfect Day, a Bay Area-based company that provides its non-animal whey protein to make ice cream, cheese, and other dairy products, has a lab inside the Singaporean research institute A*STAR. This is an expanded footprint for the company, which uses precision fermentation to create an animal-free milk protein that is identical to that made by cows. Other international agritech businesses in Singapore include Kalera, a US company that operates the largest vertical farming network in the world and is now setting up its mega farm and global R&D centre in the city-state; and Adisseo, one of the world leaders in animal nutrition and part of the Chinese Sinochem/Bluestar group. Adisseo has established its Aquaculture R&D facility on an island off mainland Singapore. In addition, some international companies are partnering with Singapore businesses to bring their products to Asia, including Oatly, a Swedish company that partnered with Yeo’s, a local food and beverage company, to produce Oatly’s eponymous oat milk for the Asia-Pacific market.

“EDB partners with our network of global leaders and other government agencies in Singapore to create a collaborative environment for companies to get started, pilot new innovations, and explore new areas of collaboration,” Chan says. “These initiatives have helped Singapore forge a close-knit, pro-business environment for agri-food players on our small island.”

In addition to more established companies, Singapore is helping to launch a range of food-tech startups, including VertiVegies, an indoor vertical farming outfit, and TurtleTree, which is the category leader in sustainable bioactive milk products. And with the Singapore Food Agency, the country is taking steps to decrease its food importation and create new opportunities in agriculture. In 2020, for instance, the SFA granted the San Francisco agritech company Eat Just the world’s first approval to sell cultivated meat (in this case, chicken). A year later, the SFA granted Eat Just its second approval, allowing the company to sell new types of cultivated-chicken products like chicken breasts. And, as mentioned, the country is home to another groundbreaking company that may soon change how the world eats: Shiok Meats, the cell-based shrimp company started by Sriram and Ling.

The first step in cultivating shrimp is also perhaps the hardest: creating a database of the crustacean’s cellular structure.

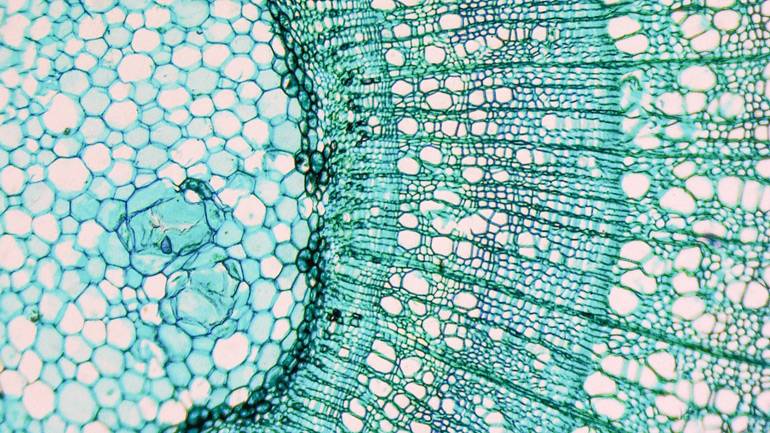

Similar to the process of growing fruits or vegetables in greenhouses, in which plants are often started from the cuttings of other plants, cultivated meats are produced from small samples of live animal cells that produce muscle and fat. But to do that, scientists first need a complete database of an animal’s cellular composition. For years, companies have studied red and white meats, like beef or chicken, creating a database for scientists to use. But shrimp had never been examined, which meant Shiok Meats needed to start that database from scratch.

First, the scientists at Shiok Meats had to isolate the muscle and fat cells from a live animal. Some of the shrimp’s genome had been sequenced by researchers, but it hadn’t been completely annotated. Sriram and Ling began isolating muscle and fat stem-cell lines, which can continuously replenish the muscle and fat tissues that make up the body. This is not an easy process. Scientists must derive the stem cells from a live animal, as the stem cells are sensitive to their growth substrate and require different sets of stimulants to proliferate. Deriving the stem-cell line for cattle, for instance, was only first achieved in 2018, and finding the lines for different species remains the greatest hurdle to cell-based meat. After years of trial and error, however, Sriram and Ling managed to create a map to cultivate the muscle and fat from a shrimp.

“We tweaked and optimised until we figured it out,” Ling says. “Each one of these challenges was like a PhD project on its own, but we finally had our map.”

Next, the scientists at Shiok Meats had to create a nutrient-rich environment to produce the cultivated shrimp. Grown in bioreactors (also known as cultivators) that look like blenders, the environment mimics the internal process and liquid flow of an animal’s body by continuously stirring stem cells in an oxygenated blend of nutrients and proteins to turn into fat and muscle. While scientists understand how to perform this process with red meats, the Shiok scientists had to forge their own way. Red meats, for instance, are cultivated at 98 degrees Fahrenheit. Nobody knew what temperature was needed to grow cells for shrimp. After experimenting, the Shiok scientists found the perfect temperature: a surprisingly cool 68 degrees Fahrenheit. This was a fortuitous discovery, because the cooler temperatures may require less energy than other cultivated meats, potentially enabling shrimp to be grown with renewable energy in Singapore.

Having found the right temperature and composition, the scientists at Shiok Meats grew the cells in larger and larger stainless-steel cultivators, ultimately creating two different food products. First, they had the meat: a paste similar to minced shrimp, perfect for dumplings and shrimp cakes. Second, they had a liquid broth, rich in nutrients that could be ideal for seasoning.

“Essentially, we created zero-waste shrimp,” Sriram says. “Everything we put into the shrimp came back as food.”

In the wake of approving cell-cultured chicken meat for sale, Singapore is poised to continue leading the world in food technology. To help Eat Just expand for the long term, for instance, the EDB supported the setup of a US$120 million plant-protein facility for the company and its consortium partners to develop its food product for Asia, JUST Egg. Made from mung bean—a bean common throughout Asia and often used for desserts—JUST Egg has five grams of protein per serving, no cholesterol, and the same texture and taste of chicken eggs when scrambled in a pan. When operational, the facility will be Eat Just’s largest facility globally and its first in Asia. As a foothold into the larger Asian market, Singapore is helping Eat Just and other companies grow their offerings for the future.

“Asia is likely to be a key market for agri-food companies,” Chan says. “With Singapore’s skilled talent pool, a diverse range of ecosystem partners, and strategic location in the heart of Asia, the country can serve as a launchpad for the region.”

A key to Singapore’s success is its forward-thinking framework for the regulation of novel food products. The regulatory process for the cultivated chicken bites made by Eat Just, for example, was stringent. SFA hired a panel of independent experts to assess the cell-based meat, the manufacturing process to produce it, and the potential for pathogenic contamination. Ultimately, the chicken bites—composed of up to 75 percent cultivated meat and 25 percent plant-based ingredients—passed approval for sale in restaurants. Building on this success, the country encourages international companies to collaborate with them early in their safety assessment processes. Singapore’s first-of-its-kind framework even provides information on the food safety assessment criteria for cultured meat and other “novel food products”—guidance that’s not currently found in many other countries, including the United States.

The impact of this groundwork is clear: Singapore is attracting the attention of a host of agritech companies, and inspiring other countries to make similar regulatory moves. Japan, for instance, recently convened a national group to start creating rules for cell-based food. “It is imperative that companies and governments—production and regulation—work in concert to successfully develop effective regulatory regimes,” states a 2020 State of the Industry Report by the Good Food Institute. “Singapore’s groundbreaking approval of Eat Just’s cultivated-chicken product puts the Asia Pacific region at the leading edge as an architect of novel and progressive oversight of cultivated meat.”

Already on its way to regulatory approval, Shiok Meats is in the final phases of research and development and plans to launch its shrimp commercially in restaurants in 2023. The current iterations are expensive to produce, at about US$400 a pound. But Sriram and Ling are aiming to drop the price to US$25 a pound and believe the cost will decrease even further as it becomes more popular. Shiok Meats is also experimenting with different technologies to enhance the product for the future, combining food science and tissue engineering to potentially create shrimp that will mimic wild-caught meat in look and texture as well as taste.

Ultimately, startups like Shiok Meats will continue to cement Singapore as the global leader in cultivated meat, helping to create a greener and tastier future for the planet.

“A decade from now, cultivated seafood and meat will be in farmers markets, grocery stores, and restaurants everywhere,” Ling says. “I look forward to continuing to play a role in creating sustainable food that helps the planet.”

*This story was produced by WIRED Brand Lab for the Singapore Economic Development Board.*