Watch and pace

The grand vision shared by Tan of Surbana Jurong is for Singapore’s leading oil and gas trading hub status to evolve to cover future-relevant “molecules and electrons”.

“We have to go back to where we started. We have no oil and gas reserves, yet we are a major trading hub. That kind of concept must have a comeback,” he said.

By “electrons”, Tan envisions Singapore’s possible role in setting up transnational grids across Asia to transport renewable electricity powered by solar, wind, or hydropower, replicating what Europe has managed to achieve.

“If everybody brings their socket here and plugs in, then you’ll have a means to move electrons as and when you want,” he added.

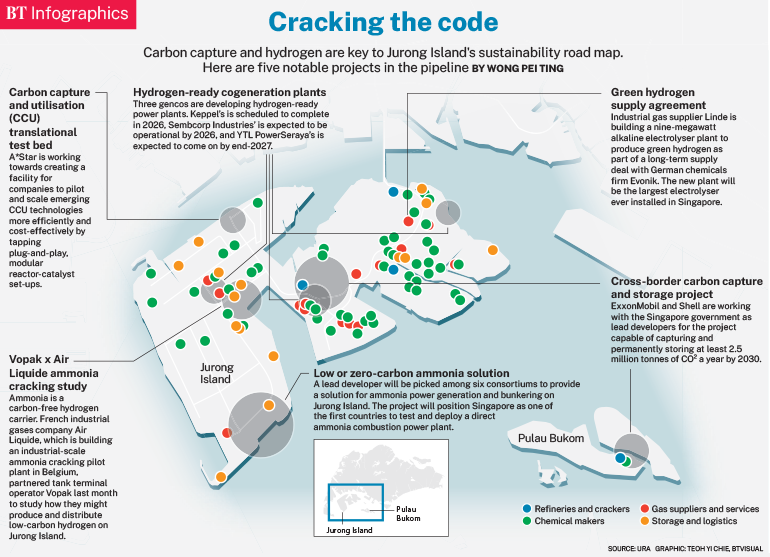

As for molecules, Jurong Island might not be where green hydrogen or ammonia is produced, but it could surely play a role in aggregating supply, owing to its mature ecosystem of storage, logistics and trade players, he pointed out.

The only thing missing now is the infrastructure, he argued.

Yet, aligning investments and, more critically, investment pace, is the priority of Jurong Island’s largest independent tank-storage operator, Vopak. In 2013, Vopak built Singapore’s first ammonia tank – which has remained the island’s only such installation after all these years.

Vopak Terminals Singapore’s president Rob Boudestijn said the storage business is capital intensive, so every investment has to be backed by customer contracts and long-term trends.

Within the maritime industry, the winds are first shifting in favour of fossil-blended biofuels, so Vopak has gone only as far as to repurpose assets previously used to store and move 40,000 cubic metres of petroleum products for its use. The next bunker fuel in line will be methanol, with the number of methanol ships on order growing, Boudestijn said.

Ammonia will take a while longer. The number of players experienced in handling it remains small, with just a 20-million-tonne fraction of the lot traded by sea annually, he added.

While some form of storage and handling standards are in place, they are not developed to the extent seen in the oil and gas industry, where products are handled in large volumes daily, he said.

He reckoned that it will take some years yet for ammonia to emerge as a widely traded commodity, as was the case for liquefied natural gas.

Undying propositions?

All things considered, Lim of EDB said Jurong Island has to host a confluence of future-ready solutions – be they carbon capture, low-carbon hydrogen, renewables, or energy-storage systems – to attract new companies making sustainable products.

These could be the likes of Arkema and Neste, which are substituting fossil fuels with bio-based feedstock centred around plants, animals, microorganisms, or fungi.

Why would Jurong Island draw these players, which would most likely have to import their bio-feedstock for further processing here? Would it not make more sense to situate their operations near the plant mills, for instance?

Lim said in return: “How do we set up our oil refineries? We never had access to crude.”

Would Singapore have to struggle to replicate its success story with bio-materials or used cooking oil, which come in much smaller qualities and are more varied in type?

Lim contended that the factors raised are precisely why the country would retain its competitive advantage, given supply chain complexities.

“There is no single location that can generate enough feedstock to baseload a biorefinery,” he said. “It would require feedstock from all over the world… from Malaysia, Indonesia, China, Australia, and New Zealand. Then you’ll have enough.”

In the case of used cooking oil, the case is even stronger for volumes to be consolidated and processed before shipping it to the end market, as up to 40 per cent of the feedstock could be lost to inefficient production, Lim said.

In fact, some of the units found on Jurong Island today can be converted to deal with biomass as the production process concerns a similar hydrogenation process used by refineries to produce fuel, he pointed out.