A successful innovation is an initiative that can deliver real value to the business and its customers… at scale. Yet only 20 per cent of new businesses launched by corporates will succeed in scaling. In fact, achieving scale with innovations in processes, products, or services is often cited as the “number one barrier to realising commercial goals.” Why is it that large corporates, with such deep experience in operating at scale, struggle to bring promising innovations to a similar level? Part of the answer lies in the third question of corporate innovation — do we have a Path to Win?

This is the third and final in a three-part series. In our first post, The Right to Win we focused on how to identify and leverage true unfair advantages when creating new products, business models, and ventures. In our second piece, The Desire to Win we discussed how innovation initiatives can win and maintain organisational support.

The Third Question of Corporate Innovation

Avoiding the widespread problem of “Innovation Theatre,” which eats up precious time and resources while producing few concrete results, can be avoided by understanding a corporate’s unfair advantage (its “Right to Win”) and how it fits into their growth strategy (its “Desire to Win”). However, to achieve real commercial success, the business has to have a clear “Path to Win” that carries a promising innovation from concept to scale, including alignment on four key areas:

- Commit and Let Go — Having gone through the setup phase of the corporate venture, a specific set of decisions would have been made. Specifically, your venture should have a great founder, the venture should have some resources to achieve its business plan and there is clarity on governance. As such, it is important to let the venture go and perform.

- Strategic Goals — As the venture operates and performs above, it is important for the corporation to review its own progress within its strategy and how the venture fits within it. We often find that while decisions to spin in or spin out seem right at the time, the corporate own strategic changes as well as the venture progress which might pivot over time might require a change of decision.

- Follow Through — As the above actions are pursued, a decision will emerge, and once it does, it is important for the corporate to follow through with it. A “Spinning in” decision requires negotiating with the founder (and evaluating whether the founder will now become an employee) while “spinning out” requires fast engagement with external investors who are apprehensive about a corporate-controlled venture.

- Lead from the Board — Throughout the process above, it is important for the corporate to lead from the board, i.e., let the venture operate within the agreed plan but maintain a close watch on how it grows and evolves. The board then is able to be ahead of any changes in direction and can help better manage resources for the venture or support its engagement with the corporate base.

Alignment around each of these areas is critical for ensuring that innovation initiatives can gain traction and grow using the best approaches with the right support.

Pressed for time? Scroll to the end of the article for a quick summary!

1. Commit and Let Go

For an innovation initiative, the transition from exploration to scaling requires a balance between support from the corporate to help accelerate growth and freedom to continue testing and adapting. More specifically, this means committing to the required investment and agreed-upon governance structure and then letting go of both tactical and strategic control. For this to be successful, organisations must have aligned on key priorities, metrics and governance approaches as we discussed in Desire to Win.

When a new initiative is aligned with business and properly incentivised, having operation freedom allows for faster and better decision-making. This is especially powerful when the initiative is being run as an independent venture with equity-aligned founders, which is the preferred approach of Wright Partners and something we have discussed in our previous articles. With incentives aligned through equity stakes in the venture, the founding team will be encouraged to make decisions that drive progress and growth, including challenging core assumptions and making strategic pivots when necessary. With a clear, approved budget, the founders can ensure they are utilising a limited budget in the most effective manner.

“Letting Go,” however, can be difficult for corporations and requires them to think like an investor rather than a day-to-day operator. This mindset needs to be applied at a Strategic, Tactical and Operational level. Strategically, the company operates in a stage-gated process where they keep control of only the high-level decisions and allow the venture substantial independence.

Tactically, they ensure the venture has the right founding team and the right interface with the organisation. Finally, Operationally, they are hands-off and focus on capturing learnings rather than creating bureaucracy.

2. Review Strategic Goals

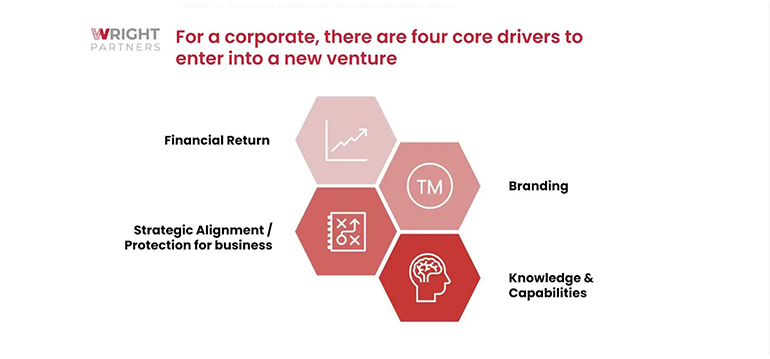

Once a venture is up and running, it’s important for a corporation to review its strategic goals for venturing building. As the corporate progresses against its own goals and as a venture potentially pivots and adapts, decisions around whether to spin in or spin out an innovation initiative can change. There are four key drivers of venture building that need to be weighed when deciding the future of a specific venture:

A. Financial Returns

There is a core tension in investing and growing innovations as a corporate. Many large multinational companies are accustomed to launching brand extensions that can quickly scale to millions of units or millions of dollars in revenue. However, innovations at the 2nd or 3rd horizon can often take longer to gain traction and scale, which leads many innovation leaders to claim that financial returns are less important in decision-making than other factors. Unfortunately, this approach is often what leads to innovation initiatives being first on the chopping block when cost-cutting occurs.

Instead, corporates need to be clear on what their financial expectations are for new innovations and how that will impact their decisions on scaling. For instance, if a new venture is able to tap into a lucrative new market or can provide a return-on-investment superior to the core business, will it be spun back in (in the case that it is an independent venture) so that the company can capture the new profit opportunity? Or would the initiative be spun out (or remain independent) so that it could leverage external funding and validation from VCs to scale without further corporate investment while still returning equity value? Clarity on the path to financial returns will help strengthen the case for investing in new innovations.

B. Branding

Although Innovation Theatre, where a company dedicates substantial resources to running “innovation” activities that produce few concrete results, is often derided as a waste of resources, there are often tangible benefits to being seen as an innovative company. In 2014, Piyush Gupta, the CEO of DBS bank, realised that they had to change the narrative around banking to avoid being disrupted and displaced by the big tech companies. By focusing on initiatives to become the “Best Digital Bank in the World,” DBS was able to dramatically expand its consumer base while also creating an ecosystem of players that wanted to work with a “financial innovator.” This market perception creates a self-reinforcing, positive feedback loop, enticing other players to want to partner with the corporate, giving them more options to drive innovation, and further improving their reputation in the market.

In this case, spinning in ventures and incorporating them into the core business may be less important than continuing to develop new solutions. In fact, keeping ventures external and having external validation from VCs may increase a corporate’s innovation reputation while allowing them to scale with less overall investment from the company.

Executives from companies that are actively building ventures in Singapore, share corporate venturing tips gained from their journey thus far. Gain more insights.

C. Strategic Alignment

Probably the most commonly cited reason for innovating is to protect the core business from disruption. In this case, innovation is strategically aligned with the future of the business. These initiatives are often kept internal, given their goal of being incorporated into or even replacing existing business units. However, they can work as well, if not better, as external ventures.

Often strategic innovations are exploring new markets, products or business models, which could disrupt existing processes. By keeping these experiments initially external and then spinning them in, the corporate can experiment with new ideas while protecting the core. It can frequently do this at a much lower cost than working with expensive external consultants and much faster than working with internal employees who might not be incentivised or have the mindset to carry on and execute such ventures. What we often see as well is that internal founders both expect their salary, benefits, and comfort from their original position to carry on into the much riskier venture as well as are uncomfortable with taking things from zero to one. Imagine the high-flying VP who is used to running a half-a-billion-dollar division with tens or more employees being asked to do the initial sales for a product that has not been validated. It’s a very large gap that is often at the core of why internal corporate innovation efforts fail.

An external venture that is properly risk-aligned also helps to maintain strategic alignment while minimising financial investment. At Wright Partners, we often compare an external venture build to the example of using a consultant to drive innovation internally. A corporate can easily spend USD $7MM to $10MM on a consulting firm for a 12 to 18 months engagement (not including its own operational and corporate costs) and that firm has no stake in ensuring that the venture works and is therefore not risk aligned. At Wright Partners, we take equity in what we build to ensure alignment and benchmark ourselves to ventures in the wild, which spend about USD $2MM over two years. Our model also focuses on attracting real founders that are aligned with equity, like us. Assuming the venture is successful AND the corporate wants to spin it back in, buying 50 per cent of equity in the venture for about USD $5MM, is still likely cheaper than having built internally while also ensuring that the corporate and the venture have strategic alignment before the spin in decisions are made.

D. Knowledge and Capabilities

Traditionally there were only three ways to develop new capabilities in an organisation. Developing internal training programs (which were often time-consuming and sub-par), outsourcing training and skills development to consultants (that were often expensive), or acquiring new capabilities through hiring (which could also be expensive and could result in a cultural misfit).

Building external, independent ventures, however, offers a fast, cost-effective way of exploring new spaces and developing new capabilities. By keeping innovations outside of daily operations, the new venture can experiment with new business models in new spaces without impacting the core business. This can result in critical insights into new approaches, processes, and opportunities that can be incorporated into the business even if the venture does not succeed. Plus, talented, experienced individuals recruited into the venture can potentially be brought into the core as part of a spin-in.

3. Follow Through on Decisions

Reviewing the key goals of venture building, as described above, should yield a clear decision on the next steps for a new initiative. No matter whether the decision is to spin in or spin out an existing venture, the corporate needs to commit to clear next steps. Innovations suffocate and die when they get wrapped up in corporate red tape.

If the venture is to exist independently from the business, then the company needs to move quickly to engage external investors. Assuming that the proper equity structure and incentives have been created, the venture will be best validated by receiving VC investment. This will allow the venture to scale without further funding from the corporate parent. The corporate parent will also gain substantial financial upside from the growth in valuation, even as their stake is diluted by future investment.

If the venture is brought into the business, then negotiations with the founding team need to be clearly defined. As mentioned above, acquisition costs for an external venture are likely to be substantially lower when considering alternatives and more so when considering the ability of an external venture to move faster and achieve more than an internal innovation experiment. However, a clear path for integrating a new business and new team must be part of a spin-in plan.

4. Lead from the Board

Overburdening a new initiative with bureaucracy and reporting can quickly stifle it. This is true to varying degrees across the innovation spectrum. Ideas that are close to the core do need tight monitoring to reduce the risk of business disruption and customer confusion. However, that has to be balanced against the need for rapid iteration and learning–requiring faster and more frequent decision-making than many operational units are used to. The farther out a new business is, though, the higher the potential friction and the greater need for freedom.

The organisational design and operating models of large corporates and corporate start-ups are largely incompatible. Core operations operate on defined processes focused on efficiency and standardisation with little room for error. As such governance models used by most companies will not work for a venture that is operating in a new market that needs space to experiment, fail, learn and adapt. This becomes particularly difficult when a venture is ready to scale. As it gains traction in the market and investment levels increase, there is a desire to manage the venture like a growing business unit–but, as we have mentioned, growth is not the same as scale-up.

Below you will find examples of how to manage from the board as we learn from venture capital firms and our own experience:

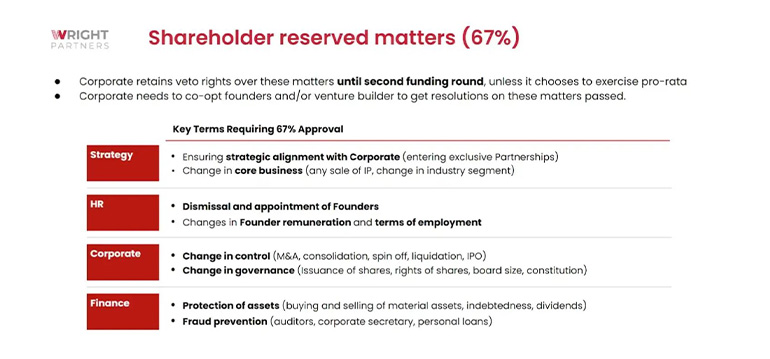

So how do you manage a venture in scale-up? The same way an investor manages a start-up, focus on strategic decisions and let the start-up do the rest. We have written in-depth on Corporate Governance for Venturing Building, but a few key points to highlight:

- Set Clear Limits — Focus on creating boundaries (i.e. total capital spend) that the business is comfortable with while giving the venture freedom to experiment as and how they need

- Think Like a Shareholder — Maintain control over critical decisions (like IP rights) while allowing the team to control decision-making outside of corporate approval processes

- Align Incentives — Aligning the team’s incentives with the success of the venture, as we discussed above, will ensure decision-making that is in the best interest of the venture

Path to Win in Corporate Venture Building

Wright Partners emphasises an external venture building model that addresses each aspect of building a “Path to Win” by maintaining optionality.

Commit and Let Go — Wright Partners focuses on building independent ventures with equity-incentivised founders and investor-like controls for corporates that allow them to give the venture independence.

Optionality to Address Strategic Goals — By starting with an independent venture, corporates have the option to choose to spin-in a business that is mission-critical at a lower price than a consulting-led initiative or keep a new venture external to raise funds and scale from outside funds.

Decision Making — We work with corporate boards to evaluate and decide the future direction of ventures before it becomes a limiting factor in their growth.

Lead from the Board — Our corporate partners act like VCs or investors would. They retain the rights to control major strategic and financial decisions but otherwise leave the management of the venture to the founding team.

Ultimately, our approach is to allow corporates to learn as much as possible by externalising as much risk as possible. If you are interested in learning more you can read our previous articles about the Right to Win and the Desire to Win.

In Summary…

Achieving scale is one of the most difficult aspects of corporate innovation. In fact, only 20 per cent of new businesses will succeed. As part of our ongoing series, we lay out the key steps towards building a Path to Win, including:

- Commit and Let Go — Once a venture is set up, commit to the operating model and give the team the time and freedom to execute the idea

- Review Strategic Goals — Review the drivers of your innovation strategy–Financial Returns, Branding, Strategic Alignment, and Knowledge and Capabilities–and the role the venture plays in supporting them

- Follow Through on Next Steps — If the venture is to remain independent, actively seek validation from external investors and, if it is to spin back in, ensure that the integration/acquisition process is clearly defined.

- Lead from the Board — No matter what the end state of the venture, put in place governance built on a VC mindset, that keeps control over key strategic decisions but empowers the team to drive day-to-day operations.

This is the third and final in a three-part series. In our first post, The Right to Win we focused on how to identify and leverage true unfair advantages when creating new products, business models, and ventures. In our second piece, The Desire to Win we discussed how innovation initiatives can win and maintain organisational support.

This article was written by Stefan Jacob, Venture Partner; and Ziv Ragowsky, Founding Partner; both at Wright Partners.

Wright Partners (in partnership with MING Labs) is an appointed venture studio of EDB’s Corporate Venture Launchpad programme enabling companies to incubate and launch a new venture from Singapore.

Through the programme, participating companies can look forward to partnering with EDB New Ventures, the corporate venturing arm of EDB, and an appointed venture studio with corporate venture building expertise and experience, to nurture their venture concepts and scale for success.