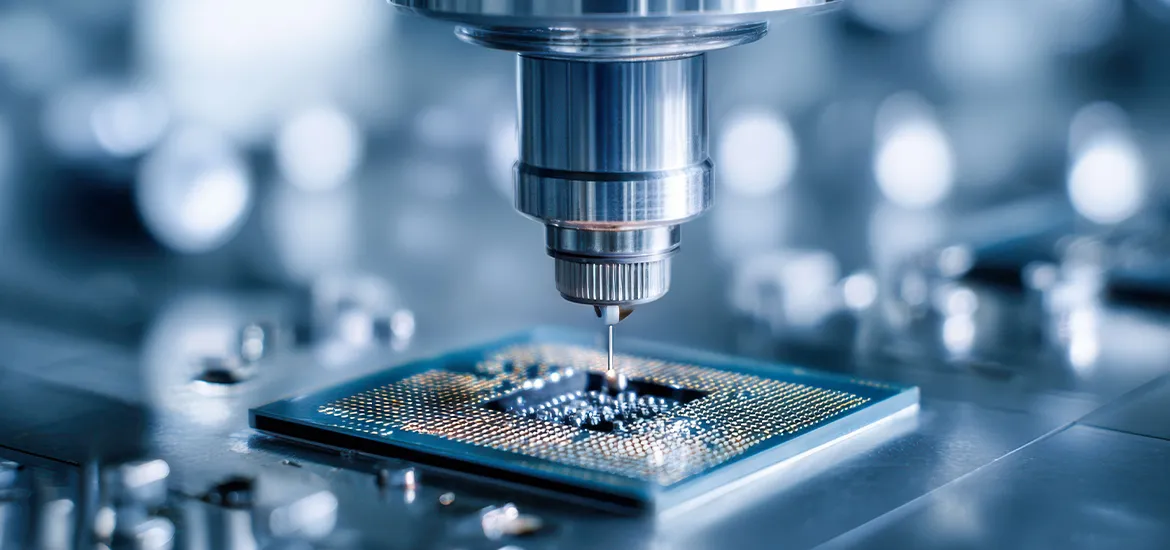

The explosive growth of generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) has started to spread out from data centres to consumer devices such as smartphones and laptops that use portable flash memory chips.

This is good news for Singapore, where US memory chip giant Micron Technology manufactures about 98 per cent of its top-end flash memory chips, referred to as NAND by the industry. Singapore, hence, is designated by the company as its NAND Centre of Excellence.

Mr Manish Bhatia, Micron’s executive vice- president of global operations, said the proliferation of AI-enabled consumer devices in the past couple of years is feeding the demand for long-term data storage – a task NAND chips are made for.

First, AI applications in most new smartphones and personal computers (PCs) – both desktops and laptops – are generating more and more data, and hence these devices need NAND chips to store content such as videos and images.

Then, as this AI-generated data is placed on the cloud, it is increasing the need for data centres to have storage capacity that runs on low power. For that, the best solution is solid state drives (SSDs) that are also made of NAND chips.

“We’re seeing growing demand for AI-enabled PCs and smartphones... which will start to generate more videos, more content,” he said in an interview with The Straits Times.

“So NAND is definitely starting to see demand drivers coming back again,” added Mr Bhatia, who is responsible for the company’s end-to end operations worldwide.

He is also a board member of Singapore’s Economic Development Board (EDB), and was awarded the Public Service Medal (Friends of Singapore) in 2024 for his contributions to the semiconductor industry.